Select publications. For a complete list, see CV.

Current Project: Envisioned Communities: Colonies, Empires, and the Visual Culture of the British Atlantic, 1620-1776 (book manuscript)

Colonial-era prints have been most often designated either “British” or “American” based on where the print maker worked or the subject matter represented. In this study, I favor of an oceanic perspective so as to argue that colonial period engravings and mezzotints served to foster and maintain a sense of community among British colonists separated by thousands of miles of open water. The study looks at both the translatlantic circulation of prints and, more importantly, how the imagery of specific prints conveyed messages of community, allegiance, and power.

“A Digital Archaeology of Saloons and Saloonkeepers,” contribution to “Roundtable on Pedagogy, Jules Prown: Reflections on Teaching American Art History.” Panorama: Journal of the Association of Historians of American Art. 2:1 (Summer 2016) journalpanorama.org

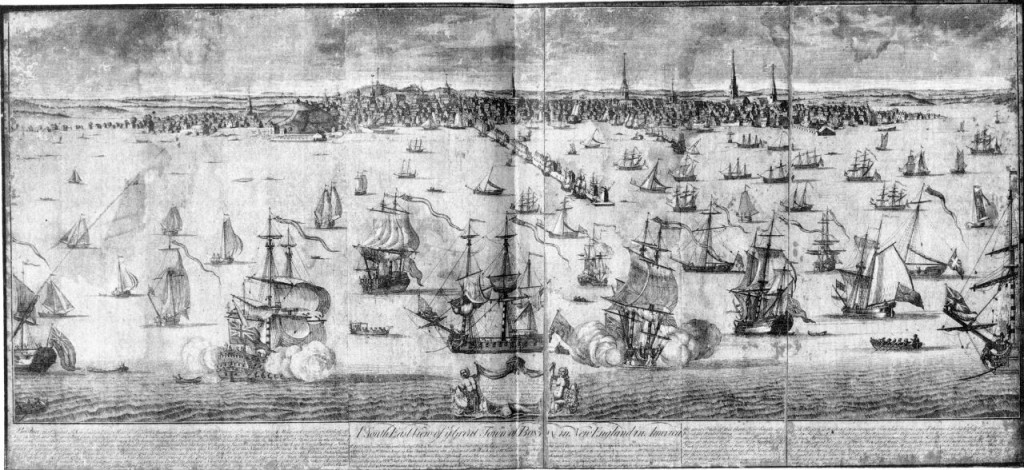

“Navigation, Vision, and Empire: Eighteenth-Century Engraved Views of Boston in a British Atlantic Context.” In New Views of New England, Studies in Material and Visual Culture, eds. Martha J. McNamara and Georgia B. Barnhill. Boston: Colonial Society of Massachusetts, 2012. 47-68.

Abstract: William Burgis’s 1725 engraving, “South East View of ye Great Town of Boston in New England in America,” often discussed as a record of Boston’s urban topography, also reveals the workings of an eighteenth-century British “imperial eye,” a vision conditioned by early modern navigational motives and technologies. By depicting Boston from a viewpoint far back in its busy, ship-filled harbor, the print emphasizes Boston not as a locale defined by land-based architecture, but rather a place positioned in time and space by maritime units of measure. In turn, when Burgis’s print, as well as its subsequent versions and copies, including one by Paul Revere, is situated within the context of the visual culture of the eighteenth-century Atlantic world, we can comprehend how such prints enabled contemporary beholders to triangulate Boston’s position in a world defined by maritime trade.

Book Review: H-Net Reviews; Journal for Eighteenth-Century Studies

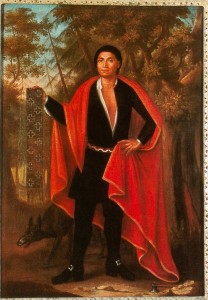

After John Verelst, Tee Yee Neen Ho Ga Row (baptized Hendrick), Emperor of the Six Nations, Mezzotint, 1710.

John Verelst. Tejonihokarawa (baptized Hendrick). Named Tee Yee Neen Ho Ga Row, Emperor of the Six Nations. Oil on Canvas. 1710. Library and Archives Canada, acc. no. 1977-35-4. Acquired with a special grant from the Canadian Government in 1977.

From Palace to Longhouse: Portraits of the Four Indian Kings in a Trans-AtlanticContext.” American Art Journal, 22/3 (Fall 2008), 26-49.

Abstract:This essay investigates the transatlantic distribution and reception of John Verelst’s portraits of “The Four Indian Kings,” four Native Americans brought to London by English colonists in 1710 and, once there, treated as visiting royalty. It argues that the imagery of these portraits was shaped by a number of artist and non-artistic factors, including the unprecedented nature of the commission, the actual status of the men who were called “Indian Kings,” and the imbalance of power between the Iroquois and European powers in North America. In reflecting these many conditions, the finished portraits possessed a remarkable polyvalency, making them useful as tools of imperial diplomacy, a role they served once mezzotint reproductions were distributed in North America among Iroquois headmen, British colonists, and Native Americans. Each of these parties, I argue, read the portraits somewhat differently, depending on their interests and objectives, but ultimately all understood that the portraits visualized the material benefits of upholding – and the potentially fatal consequences of breaking – the alliance established between the Crown and the Iroquois.

“Pelts and Power, Mohawks and Myth: Benjamin West’s Portrait of Guy Johnson,” Winterthur Portfolio: A Journal of American Material Culture, 40:1 (2005), 47-75.

Abstract: Guy Johnson had only recently been appointed Superintendent of Indian Affairs for Britain’s northern colonies when he traveled to London in 1776 and commissioned a full-length portrait of himself dressed in Mohawk garb from the artist Benjamin West. This essay interprets the masculine imagery of this unusual portrait as a direct response to the unprecedented challenges Johnson faced as a loyalist in charge of upholding the Crown’s policies at a time of revolution. Seen in this light, the portrait mythologies Johnson as possessing those masculine attributes that would permit him and his heirs to continue to live as elites in a British North America.

Catalog entries in Tim Burgard, et. al. Masterworks of American Painting at the de Young. San Francisco: M. H. de Young Museum, 2005.

“George Caleb Bingham, Boatmen on the Missouri: Paddle Wheels of Commerce,”86-89.

“George Caleb Bingham, Country Politician: Talking Politics,” 90-93.

“Winslow Homer, The Bright Side: Truth and Humor,” 155-58.

“William Glackens, May Day in Central Park: Making Americans Under the May-Pole,” 259-62.

“George Ault, The Mill Room: Aestheticization and Alienation,” 311-13.

“Arthur Dove, Sea Gull Motive: Spirit of the Sea,”323-25.

“Diego Rivera, Two Women and a Child: A Mural in Miniature,” 326-29.

“Charles Sheeler, Kitchen, Williamsburg: Geometry and Craft,” 350-53.

“Charles Biederman, Paris 140, January 14, 1937: Abstracting Nature’s Structure,”354-56.

“Charles Howard, The Progenitors: Mysterious Ancestor,” 385-87.

Reviews:

Review of Thomas Kinkade: The Artist in the Mall, Alexis L. Boylan, ed.,Durham: Duke University Press, 2011. In Cultural Analysis: An Interdisciplinary Forum on Folklore and Popular Culture, 11 (2012).

Review of Lisa Strong, Sentimental Journey: The Art of Alfred Jacob Miller, 2008. For Western Historical Quarterly, 41:1 (Spring 2010), 112-13.

Review of Micheal Guidio, Engraving the Savage: The New World and Techniques of Civilization, (2008). For CAA.reviews. 8/4/2009. www.collegeart.org

Exhibition review, “Women on the Verge: The Culture of Neurasthenia in 19th-Century American Art,” Cantor Art Center, Stanford University. For CAA.reviews. 5/9/2005. www.collegeart.org